Welcome to the inaugural post of the Mech language blog, where I will be documenting my work on the language as I go. In this first post, I will just talk a little about what the language is for, and where I’ll be taking it in the near future. You can also follow Mech’s development on Twitter (@MechLang) or by signing up for the mailing list.

What’s Mech?

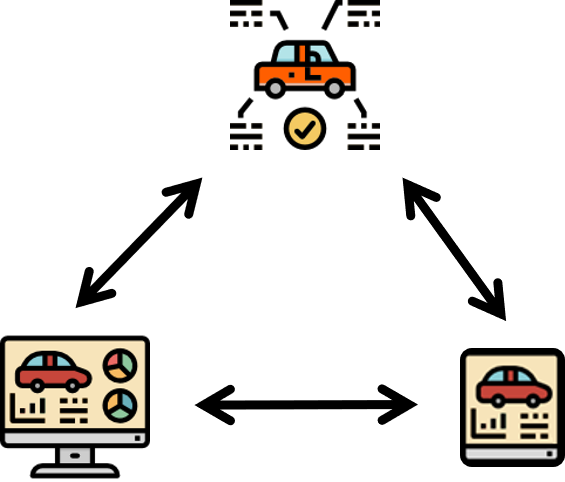

I’m developing Mech as a domain specific language for a project I’m working on, the essence of which I hope will map to problems people would like to solve in general. The project I’m working on is a system consisting of the three interconnected components:

First, I have a small robot car platform with several sensors, including a Kinect 2 and a 9-axis AHRS. These sensors stream 3D depth information about the environment, and 9D orientation information about the robot’s pose. On-board processing of this data is handled by a standard AMD x86_64 CPU.

Next, I have a tablet to which I would like to stream data from the robot. The tablet will display the sensor data, transform and filter it, and send it back to the robot. The final piece of the system is a server, which will host long-running computations like SLAM or neural net model training. The server can communicate with the tablet or the car directly. In summary, the system looks like this:

Mech is therefore a platform that allows me to work with the system described above with the minimum amount of coding. The platform should handle all the heavy lifting in terms of connecting to devices, shuffling data around, providing transforms and visualizations, and it should all be fast enough for a robotics-focused application.

(At this point many of you may be tempted to make a list of various technologies or platforms that when cobbled together could facilitate such a project. I’ll detail it in another post, but I’ve already built an off-the-shelf system that I ultimately found wanting. That’s the reason I’m building something from scratch.)

Requirements

Let’s break out the essential properties of the system I described above, so we know the important properties of the language we’re about to build.

- All streams all day - Data in this system are mostly matrices or vectors. Thus, Mech should be especially well suited to working with these data types.

- Distributed - Computation happens on loosely coupled network of computing resources. The platform should make it easy to distribute computations and data to various locations. Work is done asynchronously, at different times, at different locations, but that shouldn’t stop other work from progressing if it can.

- Real-time - both real-time in the sense that we want the most up-to-date view on data, and real-time in the sense that we want guarantees about the responsiveness of the system when we can. Mech will operate on systems like robot cars where latency does matter.

- Reactive - reacting to changes in data should be a forte of the language. You shouldn’t have to specify how data flows, but only what data is flowing. Mech should do everything for you in terms of routing and updating streams and computations.

- Time and space matter - Streams of real-world data represent the physical world, so time and space matter. Streams coming into Mech can represent a quantity – a value plus a unit. Mech should handle conversions between quantities of different scales (e.g. feet to meters). Similarly with time, Mech should handle time explicitly, allowing you to talk about the

previousornextvalues in a stream. - Visualize Everything - In a system defined by data flows, bugs are going to exist where streams are incorrectly routed or transformed. Tools capable of visualizing and inspecting streams at any point in time will make debugging this kind of program easier.

Imagine the Science Fiction

We used to do something at Eve where we would imagine a sci-fi future where we had cool computing tools. What kinds of things could we do with those, that we couldn’t do today? By imagining this future that didn’t exist in explicit terms, we could work backwards and figure out the necessary technologies to make that fiction a reality. I’m going to do the same thing here, phrased as two lists: things that an idealized Mech makes trivial, and things that it makes impossible [1]. Here’s a chance for us to think big and imagine a future where anything is possible.

Mech makes it trivial to…

- …transform data from one shape into another.

- …visualize anything in multiple ways. Tap on any variable, see its history, overlay it with other variables and track them over time.

- …track down the source of a bug. It points out exactly what piece of code is causing the error, and show the full chain of execution that generated it.

- …share programs with friends or coworkers. Click one button to host online, send a link or text to grant access to a running application.

- …record and playback everything.

- …compose code like snapping together lego bricks. For real this time.

- …scale and distribute your program with a single click.

- …explore different execution paths by allowing you to rewind an execution, change code, and then resume the execution in place.

- …rewind to the past and change the computation graph.

- …use a variety of input methods: mouse, pen, touch, voice, VR, etc.

Mech makes it impossible to…

- …write a program that can crash.

- …write a program that can deadlock.

- …corrupt memory or access uninitialized memory.

- …end up with inconsistent state.

- …get stuck at any phase of development.

Coming from today’s programming language landscape, the above may seem more on the fiction side of things. But it is my hypothesis that all of the above will be achievable with Mech, made possible by the greenfield approach we’re taking. As I’ll show in the coming blog posts, some of the decisions we make up-front about the semantics of the language will have major implications down the road on what we can achieve with tooling.

Conclusion

Hopefully now you have an idea about the spirit of Mech. This post was really about the motivation for building it and what I hope it will become one day. I hope it was enough to convince you to follow along as we build this language. In the next post I’ll talk about specifics of Mech, in terms of its architecture and the implementation as it stands so far.